Internet engineers have always known that there was no technical constraint on people using addresses that were properly registered to other users.

If there is a guiding philosophy to the internet, it could be permissionless innovation. Permissionless innovation refers to the concept that the creation of internet applications and technology should be open to grassroots innovation, unburdened by permits, regulations, or commercial negotiations. Users and operators control the devices we connect to the internet, in direct contrast to the regulatory framework of the telephone system.

The foundational principle was that an unburdened internet would allow for the greatest impact to revolutionize the internet. A prime example of this is how Tim Berners-Lee , the computer scientist regarded as “the inventor of the World Wide Web”, developed the HTTP protocols that are now used by every website – without asking for permission from internet networks. The current-day internet giants of Facebook, YouTube, and Google originated from the same ground-level experimentation to provide technological solutions autonomously.

However, the model of permissionless innovation meant that the early days of the internet were built on a foundation of mutual trust. As ARPANET (1970s) and NSFnet (1980s) evolved into the global internet of the 1990s, it was possible to accidentally or deliberately configure a network with IP addresses registered to another entity. The only restraint against intentionally using someone else’s IP address – a tactic known as IP spoofing – was etiquette, professional ethics, and a sense of operational practicality.

Without guardrails in place, as the internet expanded so did the security vulnerabilities. The door was left open for abuse, particularly through IP spoofing and Denial-of-Service (DoS) / Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) cyberattacks.

Understanding the Problem: IP Spoofing and DoS Attacks

When a network allows packets with forged source IP addresses, bad actors can exploit it to trigger DoS/DDoS or amplification attacks on other networks.

A DoS/DDoS attack floods a server with traffic with the intent of overloading it, making one or more websites unavailable to users. Domain Name System (DNS) amplification, a type of DDoS attack, exploits sends small DNS queries from spoofed IP addresses toan open DNS resolver, generating a large, amplified response from the target server, overwhelming its system.

These attacks generate an immense load of extra traffic, often taking services offline and incurring costs for mitigation. They may result in days of downtime, significant losses in revenue, halted labor productivity, and repair costs that make these threats more than a simple annoyance.

The Impact of Cyber Attacks

Over time, the internet has moved from being an interesting toy, to a convenience, and now an essential utility. Internet outages from cyberattacks can have similar economic consequences to electrical outages.

CSO online reported in 2017 that the average financial impact of an enterprise cyberattack was $1.3 million, nearly half of the cost of which was spent on internal staff wages ($207k), software and infrastructure improvements ($172k), and cybersecurity training ($153k).

Attacks, and costs have only grown in the eight years since that report was released.

According to Gartner and the20.com, a 2021 business survey seeking estimated impacts of downtime resulted in reports that a single hour of downtime can cost over $100,000 for even a small business, and $1-5 million for large enterprises.

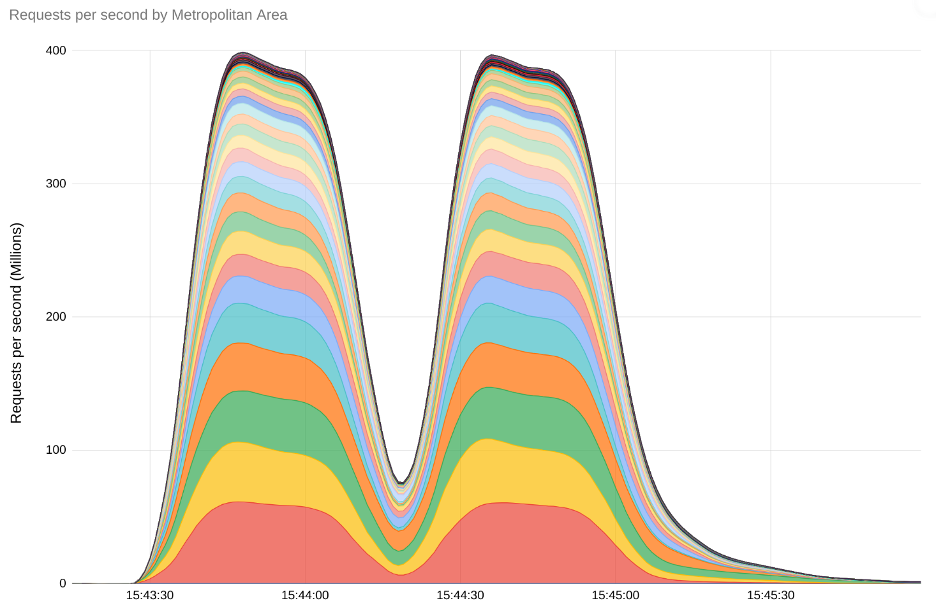

The largest DDOS attack to-date occurred in October 2023 against Google, Amazon, and Cloudflare. The attack used an HTTP/2 technique dubbed “Rapid Reset”, that repeatedly sent and canceled requests. According to a blog released by Google, the attack reached a peak of 398 million requests per second (rps) and was 7.5 times larger than the previous record, set only a year before. Google, Amazon, and Cloudflare were able to mitigate the attack, however, smaller or more vulnerable enterprises – such as financial or healthcare institutions, who are prime targets – may not be as prepared.

Image illustrating the scale of the requests per second during the attack. (Source: Google)

BCP 38: An Underused Solution

With the scale of attacks growing, attack prevention and mitigation is a necessity for current business operations. But the need was foreseen a quarter of a century ago. In 2000, a recommendation was published that proposed a simple strategy for blocking IP spoofing that could prevent many DOS attacks.

BCP 38 (RFC 2827) recommended that networks block packets with spoofed IP addresses that shouldn’t logically originate from within their domain. The principle is simple: if there’s no valid return path for a source IP address, the packet should be dropped.

Some organizations saw BCP 38 as an opportunity to not only improve routing security and reduce their own risk, but to improve revenue for special configuration charges and simplify their network. These organizations implemented measures such as Source-Address Validation through home routers and rejected traffic that used the wrong IP addresses. Networks serving small and medium sized businesses used unicast Reverse Path Forwarding (RPF) filters on their customer facing routers, preventing inbound traffic that has a source address of the inside of the network.

However, BCP 38 faced resistance in adoption, and is still not universally deployed 25 years later.

Why would a straightforward set of recommendations with clear benefits face such resistance? The reasons varied among networks:

- Customer types: Some networks had customers that legitimately used IP addresses from multiple providers

- Equipment limitations: The network’s current equipment couldn’t perform the required policy checks required to detect and filter IP source address spoofing

- Business profit: Networks that charged by the byte profited from the additional bandwidth used, even if the additional traffic was due to attacks

In short – for many businesses, they either gained revenue from the attacks or were reluctant to spend their existing capital in equipment upgrades. Business strategy directly conflicted with the engineer

’s efforts to protect ordinary internet users.

Enter MANRS – A Collaborative Industry Response

That started to change in 2014, when the Internet Society started the MANRS program, which recently transitioned to the Global Cyber Alliance in 2024.

MANRS launched with the Routing Resilience Manifesto – a set of best practices and actionable steps for network operators to follow to address common network threats, improving network security and resilience. MANRS builds on the principles of BCP 38 by providing a structured framework and visibility into participants’ security postures.

MANRS details compulsory and recommended actions addressing three types of problems:

- Prevent propagation of incorrect routing information

- Prevent traffic with spoofed source IP addresses

- Encouraging global coordination and collaboration

Actions identified as compulsory detail the minimum requirements for participants to implement, whereas recommended actions focus on addressing the root causes of DDOS attacks and encouraging cryptographic validation measures.

Sensitive to the pitfalls of BCP 38 implementation, MANRS compiled their list of action items based on established best-practices, and provides care to balance changes with small, incremental costs that smooth the financial aspects of implantation for small operations with larger measures that contribute greater common benefits.

MANRS And Related Efforts Today

MANRS has now been operating for over a decade. Although MANRS started with network operators it has evolved to include every branch of networking.

Today, MANRS includes tailored programs for:

- Network Operators

- Internet Exchange Points (IXPs)

- Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) and Cloud Providers

- Equipment Vendors

The program types interlink with each other through a “belt and suspenders” model that supports and improves the effectiveness of each system for those who participate:

- Equipment vendors provide features like source address validation and RPKI to support implementation by other participants, beneficially enhancing their brand reputation

- IXPs are required to implement route server announcements filtered based on Internet Routing Registry (IRR) and Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) data— simplifying route sharing by enabling a single configured peering to support routes across all peers.

- All networks benefit from choosing vendors and peers who are already MANRS-compliant.

This approach ensures that improvements in one area benefit the entire internet community.

Heavy emphasis is also given to community participation. MANRS publishes the names of participating networks – giving weight to the goal of public commitment, collaboration, and collective responsibility for implementation. MANRS participants aren’t just quietly implementing behind the scenes, they’re demonstrating a visible pledge. Although the list may be seen as polarizing, organizations not listed are not necessarily in opposition – the over 1,000 public participants are instead seen as forward-thinking trailblazers that raise the overall baseline for internet security.

Proof through Metrics: The MANRS Observatory

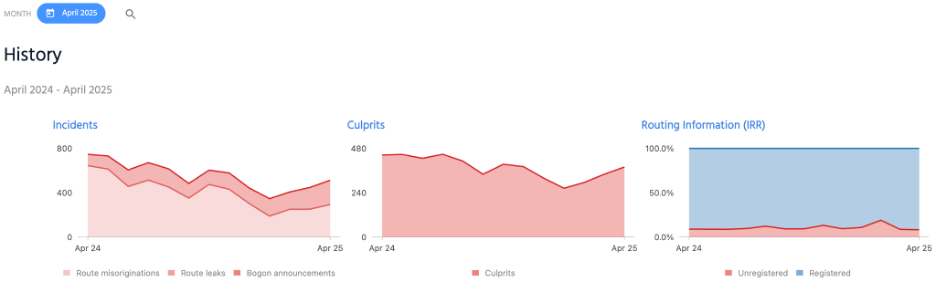

The MANRS Observatory provides real-time metrics on routing incidents and participating networks. This measures the level of MANRS readiness – how well recommendations are implemented in real-life -and also gives a sense of the overall state of routing security.

Over the past year, it has tracked a steady decline in routing misconfigurations and spoofing incidents among compliant networks—clear evidence that the framework works.

The MANRS Observatory shows a downward trend for incidents and culprits between April 2024 and April 2025.

The Role of IRRs and RPKI

Internet Routing Registries (IRRs) have also been making efforts to improve take-up on a related front using coordinated deployments through the Number Resource Organization (NRO). The NRO acts as a coordination spoke for the five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) to secure routing using Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) Resource Certification efforts. RPKI uses digital certificates to validate that the address space being used by an authorized network. Validating networks can automatically reject routes that don’t match the published digital certificate.

The published 2025 NRO RPKI Program goals include efforts to:

- Improve the transparency, robustness, and security of RPKI systems

- Deliver an increasingly consistent user experience, no matter which RIR you use

- Standardize terminology, documentation, and functionality provided by the RIRs’ user interfaces

- Address current concerns related to RPKI to align on agreed upon core features

These efforts should make deployment easier for large global networks and smaller, regional and local networks.

Recommended Steps for Businesses

MANRS participants are industry leaders, but that doesn’t mean they are the largest networks in the world. Often, they are smaller networks whose “values and practices” align with the program. And the actions aren’t necessarily hard to perform.

Here are some recommended steps you can take within your own organization:

1) Lower your own risk profile by using the MANRS participants list to inform your purchasing decisions:

- All the participating equipment vendors support the MANRS mandatory actions, so choosing a vendor from the list may meet your needs while also supporting network resilience

- If buying internet transit, select a participating network

- Select a MANRS compliant Internet Exchange Point (IXP) by checking the IXP Database (IXPDB), and prioritize peers with a Boolean “True” flag for MANRS compliance.

2. Even as a small to medium size organizations, you can take straightforward steps within your own network:

- Don’t propagate “incorrect routing information”

- Keep NOC contact information up to date in Whois records

- Configure BCP 38-compliant filters

- Publish a routing policy in IRR

- Create and maintain valid RPKI Route Origin Authorizations (ROAs)

The importance of individual organizations implementing best practices cannot be overstated, as global cyberattack trends continue to escalate. According to statista.com, the global cost of cyberattacks are estimated to increase to $13.82 trillion by 2028. Although attacks on enterprise giants get the most press, smaller attacks on various industries may cause the most impacts to businesses. Estimates indicate that a successful cyberattack with only $10,000 in financial impact would cause 20% of small-or-medium size businesses to go out of business. Global security efforts are no longer optional, but mandatory to keep your business operational.